Mickey was just like a grandpa to me. Our families have been close for three generations. Trips to Mickey’s shoe store were adventures for a little girl who he called his “little Rosie” because he thought I so closely resembled my grandma. Even though I was not raised in as small of a town as Elmwood, to me it was a magical place to visit.. This was the kind of town everyone knew everyone and no one felt the need to lock their doors. I’m pretty sure it’s the same today. I hope you enjoy dad’s tribute to a very special man. – Amy Jo

“Who was Wilbert McGuire?”

“I’ve never heard of him.” After a pause, the old-timer continued, “I once knew a guy named McGuire who ran a shoe store in Elmwood, Illinois, but I don’t think his name was Wilbert. Everybody called him ‘Mickey.’”

“Yes, that’s who I mean – Mickey McGuire, whose store was across from Central Park.”

————————-

Although Wilbert McGuire was in business over 40 years, no one ever called him “Wilbert,” as far as I know. I doubt whether his own mother called him “Wilbert,” unless he did something to upset her. And I suspect that might have happened once in a while, because he was a prankster – nothing illegal, nothing dangerous, just good fun. In his youth he may have tied tin cans to a cat’s tail, dumped an out house or two on Halloween, or told tall tales about the preacher’s wife. Genuinely good natured, Mickey would do anything for a laugh.

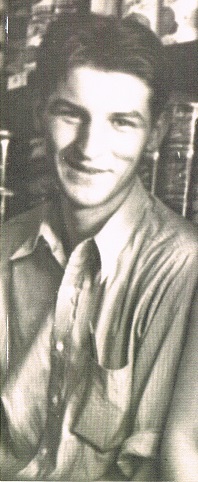

Tall, about six feet. Skinny, really gaunt. You could see the top of his collar bone sticking out of his open-necked shirt. Mickey’s most distinguishing features, however, were a long narrow nose and a large Adam’s apple. Even with a normal swallow, he looked as if he were trying to digest a golf ball lodged in his throat. His hair was long and black and seldom parted because it was so coarse, so unruly. Instead, as I recall, he used his polish-stained fingers to arrange his hair like a comb with wide teeth. He had big, bony cheeks, dimples on both sides and caramel-colored teeth – too many Camels. And that smile, that laugh.

Hundreds of times, when I visited his store, Mickey was facing the back wall, holding a shoe over a grinder or buffing the toe of a wing-tip to a high gloss. The noise could be deafening. From time to time, he would shut the machinery down, turn around facing the front of the store, and apply glue from a tin container to soles with a little brush. The smell was strong but not unpleasant. When customers took seats in one of the three or four chrome-handled chairs to try on some new shoes, Mickey took off his apron and came from behind the counter to wait on them. His two different jobs were almost incompatible: repairing shoes and selling them.

He wanted to look presentable as a salesman and so he wore a dress shirt, always open at the neck, but to repair shoes – to grind soles and polish the “uppers” as he called them – he had to wear a dark-colored apron. He never won. He always looked more like a cobbler than a shoe salesman. To be more presentable, he removed his apron to sell shoes, but his shirt and pants were usually spotted with polish above and below the apron. To tell the truth, no one cared. In the 1940s and 50s, there was less pretense. Mickey was Mickey. Our expectations were lower; our values were different. Whether he wore an apron, whether it was covered by polish, it wasn’t important. Everybody was glad to see him, to listen to one or more of his million stories, some corny, some really funny, sometimes for the first time, sometimes for the tenth.

I don’t think it was possible for Mickey to sell or repair shoes for a stranger. If he didn’t know customers when they came into the store, Mickey knew them when they left. “Where are you from?” he asked. “What does your husband do?” (Women didn’t work outside the home in those days, so it was a waste of time to ask most of them what they did.) “How many kids do you have?” When he got to know someone, especially a young woman, he’d greet her at the door and put his arm around her. “How’s my Susie Q?” he asked. Many times, I saw him put his right hand around my mother’s waist, grasp her right hand and take a dance step or two. “How’s my little Rosie?” She would smile and laugh. His behavior was innocent because, more than likely Helen, his wife, would be standing there purring, like a little kitten. She’d smile and greet customers, but otherwise, unless forced to do so, she limited her involvement in most conversations to listening and to watching. Talking was an effort.

They were a pair: he loved to talk; she listened.

On busy days like Saturdays, he’d fix shoes; she sold them. They worked long hours– from 8 am to 6 pm during the week and from 8 am to 10 pm, or until the last customer left on Saturday night. At ten o’clock, if someone looked inside the front windows, Mickey wouldn’t think of turning out the lights or telling them to leave because it was ten o’clock. Ten o’clock was a guideline, not a deadline. The customer came first. Remember, at that time no one was in a hurry. During the day, Mickey and Helen would take a break now and then. They would have long conversations with customers after a transaction, and they would break for lunch, upstairs in their living quarters. The big meal was served at noon: pork chops, mashed potatoes and gravy, lots of coffee made on the gas stove and maybe a piece of homemade cherry pie. The view from their kitchen windows reminded me of a flat in France, looking over the tar paper roof of the Penny Grocery below, the Elmwood Elevator in the distance. Then he’d take the winding stairs to the store below, pick up his dark blue apron, flip the switch on the machinery and go back to work.

During the war years, when shoes were rationed and new ones hard to find, old ones needed new soles and heels. Mickey would often return after supper, sometimes working behind a locked door until 10 or 12 pm. He could hardly keep up. Sometimes the floor behind his counter was covered with dozens, sometimes hundreds, of leather-soled shoes for workers in Building LL at Caterpillar Tractor Company, mud-covered Red Wing boots for farmers like Rolla Shaffer, or high top work shoes for miners like Raymond Metz or Stanley Winn. Despite the number to choose from, Mickey could always pick out the right pair for a customer without checking the sole where the name was embossed in chalk. What a memory!

Mickey was a hard worker, but he never worked hard. He paced himself carefully, to the extent possible, so that work was never really work. He loved his mid-afternoon walks to the post office about a block away where he’d pick up a few envelopes (one cent stamps for local delivery, three-cent stamps for out-of-town). Generally he was less interested in the envelopes than in latest issue of the Wall Street Journal.

Leaving the post office, he’d stick his head in next door at the Elmwood Café, where he’d greet some friends, like Charlie Hicks, a grocer, or Mayme Moody, the carpenter’s wife. They were sitting at tables by the window or on the round stools in front of the counter.

Mickey would take his seat on a stool, order a cup of coffee, stir it with a tin spoon and tease the teenage waitress. “Aren’t you cute today, Susie Q.” The blonde grinned. Then he’d open up the last page or two of the paper, and take his index finger down the columns of stock quotations: General Motors was 38. International Shoe was 16. CILCO was 27. And General Telephone was 33. They were all safe. They all paid a dividend. Mickey’s philosophy was simple: buy what you know. He followed his own advice: he drove a Buick four door (“shit-brindle brown,” according to my Dad), sold Rand shoes made by International Shoe, used his General Telephone dividends to pay his phone bill, and paid his monthly electric bill to CILCO. When a lineman like Richard Schrimp or Wayne Slone who worked for the power and light company came into the store, he would remind them that he was a stockholder. “Make sure you put in a good day’s work and take care of the truck we stockholders bought you.” They’d laugh, but Mickey was half serious. He worked hard; he expected others to follow his example.

As much as he enjoyed the craft he learned from his father, Mickey felt cooped up inside the four walls of his store. So when he could – in the evening or in the summer — he sprang from his cage. Sometimes by himself, with Helen or with his kids and grandkids. By himself, after dinner, he found a place to play cards with guys like Gene Bourgoin, the local monument maker; “Rasty” McKinty, the mayor; or Ralph Kilpatrick, the only accountant in town. They began a friendly game of poker – mostly for quarters and half dollars, sometimes for dollar bills. When he was lucky, he accumulated a stack of chips; when he wasn’t, he took the game for its intended purpose – a way to pass time with a few friends, and escape from the confines of the four walls.

On other evenings, Mickey and Helen would finish their supper and take long, long walks around town. Sometimes they went for miles, but they always ended up circling Central Park—under the large overhanging elms, beside Lorado Taft’s statue, “To the Pioneers.” On occasion, late on a hot summer night, they sat on a bench, watched the semis turning the corner in front of Edison Smith and Sons Hardware, talked to Harry Taylor who had just left the Penny Grocery or visited with Arno “Slim” Dauma, the one-man Elmwood Police Department. They were trying to catch a few cool breezes before they went home – upstairs above the store – to rest for another day of fixing and selling shoes. No air conditioning. Just a window fan which drew in the hot night air.

When they had more time, when their kids and grand kids were out of school, Mickey and Helen took them to the Colorado Rockies or the Gulf Coast of Florida, staying for three or four weeks.. Years passed. Mickey retired. He’d work a little now and then, to help his son and daughter-in-law, who had taken over the store, but essentially he and Helen were retired.

—————-

On January 3, 1979, my mother lost her husband. Without warning, without a clue, I lost a father. It was too cold, too snowy for a funeral: four-foot snow drifts; winds howling across the Knox County prairie; temperatures, even in the sun, ten degrees below zero. Mickey and the other pallbearers placed Dad’s coffin on the snow before us. The minister, in a hat, gloves, wool scarf and heavy overcoat, said just a few words and closed his book. Everyone left quickly.

—————-

In the spring of 1979, when the snow had been gone for several weeks, but when a light sweater felt good, I drove back to Elmwood to see my mother – to talk, to run some errands, to write some checks. When we were done and I had given her a hug, I decided to visit McGuire’s Shoe Store. Mickey was there, but no one else. He greeted me warmly, placing his left hand on my back, looking closely into my eyes. He knew I was still hurting. We had never talked after Dad’s passing; we had never talked about religion. I had seen him once or twice at church in his double breasted suit, but he never talked about God, about an afterlife. If he was religious, he kept it to himself. Out of nowhere, he began, “I went to the cemetery last week. I sat on a tomb stone and talked to Harry Taylor. I brought him up to date…” Somehow his remarks made me feel better. Don’t know why. Can’t explain it.

Nine years later, around the end of June, I remember standing outside Proctor Hospital in Peoria, Illinois, beside Mickey’s daughter, who was in tears. She said, “He’s not good. I think we’re going to lose him. I will miss him a lot.” I responded, holding back the tears, “We’ll all miss him.”

Several days later, I was at the Patterson Funeral Home, along with the other pallbearers facing the clergy who took part in the services – Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist, even Roman Catholic. I think Mickey was a Presbyterian, but that’s not important. Denominations are irrelevant at a time like that. They seem silly. Father Horne, the Catholic priest, a tiny little man of great humility and warmth, peered over the lectern and began with these words. “In the last ten years we have lost many good people, but for me two stand out – Harry Taylor, our grocer, and now Mickey McGuire, our cobbler.”

I was stunned. Father Horne continued, but I paid little attention to the rest of his words; I was thinking about a cold day in January 1979. The last words were said; the last songs were sung; everyone walked outside in the bright sunlight. Drivers in the long motorcade started their engines, “funeral” flags waving in the breeze, and we began the journey from Patterson Funeral Home to the cemetery. On the way we passed some familiar sights: Morrison and Mary Wiley Library, Jordon’s Mobil, the Palace Theater, McGuire’s Shoe Store, Armstrong’s Clothing and the Farmers State Bank. Then the motorcade rounded Central Park, not once but twice, in memory of a couple who had walked that walk, time and time again. Then we proceeded west to the cemetery.

Twenty years later, if you drove past Central Park in Elmwood and turned at Edson Smiths & Sons Hardware (now called Hometown Hardware), you’d still see “McGuire’s Shoes” painted on the building which now houses a beauty shop. If you walked up to the post office and the Café, you might find someone who remembers when shoes were sold and repaired in Elmwood. They might still be arguing whether the cobbler’s name was Wilbert or just plain “Mickey McGuire.”

Karl K. Taylor

Sept. 1, 2008

That is a well told story. I wish my children were growing up in the simplicity of your small town Elmwood.

LikeLike

Enjoyed your story of Mickey McGuire. Thank you for sharing.

LikeLike

I was born and raised in this wonderful town! Miss it so much some times. Thanks for this wonderful story!

LikeLike

Loved it! Awesome KarL.

LikeLike

What a wonderful tribute to a small-town man who because of his role as the Elmwood cobbler knew everyone who lived and worked on the western-edge of rural Peoria County. As a young child I remember visiting Mickey at the shoe store with my grandparents Harry and Edna. Mickey liked to shadowbox with me and I remember his smile was infectious and the joy of life seemed to emanate from his very being. May this tribute be a blessing to his family and friends and to all who treasure the memories of growing up in small towns – where everyone knows one another and all are loved.

LikeLike

My father-in-law was our local cobbler. Your story brought back many memories of another wonderful man.

LikeLike

I enjoyed this story a lot. Thank you, Karl.

LikeLike

Jana, I’m glad you enjoyed it.

LikeLike