In the fall of 1956, Helen Hart Metz was the only woman I knew who displayed her family name – Hart – conspicuously beside her married name: Metz. Ten years later, when women were burning their bras in the big cities and standing up for their rights, women like Betty Friedan and others encouraged women to retain their family names rather than to take their husbands’ names when they were married. In the 1960s and 1970s, still other women, often called “women’s libers,” combined their family and married names, placing a hyphen between them like Helen Hart-Metz.

In the fall of 1956, Helen Hart Metz was the only woman I knew who displayed her family name – Hart – conspicuously beside her married name: Metz. Ten years later, when women were burning their bras in the big cities and standing up for their rights, women like Betty Friedan and others encouraged women to retain their family names rather than to take their husbands’ names when they were married. In the 1960s and 1970s, still other women, often called “women’s libers,” combined their family and married names, placing a hyphen between them like Helen Hart-Metz.

Helen was, in many ways, a “women’s liber” before Betty Friedan invented the term. I’m sure she never burned any bras, but it was not unusual to see her in social situations in her home, wearing a man’s white t-shirt, no bra, smoking one Benson Hedges cigarette after another without inhaling, and drinking a can of beer. In a small conservative country town in the Middle West in the 1950s, Helen was, to some people, at least daring, maybe brash and perhaps “uppity.” Her behavior, her demeanor made a statement. For some, she was a refreshing breeze; for others, she was too liberal, maybe even radical, for a town with one authentic tavern (not counting the VFW) and half a dozen churches filled every Sunday morning.

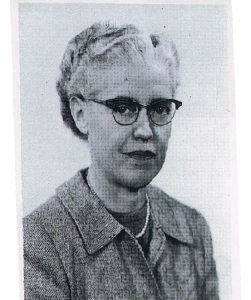

Fairly short and skinny, she wore dress slacks whenever possible at a time when most women didn’t own a pair. Her hair, very gray, almost white in her late forties, was always short. Some people said Helen reminded them of Bette Davis, the famous actress: similar figures, the sexy eyes, the guarded smile. Hearing that remark, she made a point of watching Davis in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane to see, in fact, if she saw a resemblance. I saw one. She never said.

Helen Metz was born in Elmwood around 1908, graduating at or near the top of her class, one of the few females at the time who attended college. She dated widely and had a reputation for being a bit wild, whatever that meant more than 75 years ago – probably keeping the hem of her skirt a little high, her lipstick a little redder than good girls were allowed, her hair bobbed when church girls wore theirs long, and the only woman in town, young or old, who smoked, at least publicly. She dated tall men, short men, skinny men, fat men, talkative ones, and quiet ones. She ended up marrying Raymond Metz, an average-sized quiet one, who learned to fly private planes for the fun of it (scared her to death), but became a shovel operator for Peabody Coal Company for a livelihood. He was mechanical, using what he learned in Mechanics Illustrated. In off hours, he worked on cars, fixed TV sets, and even designed and installed radiant heating in their first apartment. He had to keep busy; they had no children. No one could ever figure out what they had in common, but they seemed happy.

As far as I know, Helen never read Mechanics Illustrated. She enjoyed the classics like Chaucer and Beowulf, the great historians like Durant, Morison, and Schlesinger and was not afraid to venture into the writings of biologists and mathematicians, long before she went off to college. She was a Civil War buff, reading all the great historians and visiting the principal battlefields. She even did editorial work for J.G. Randle and his wife, University of Illinois Lincoln scholars and for Hazel Wolf who wrote the Blue and Gray on the Nile. A Renaissance woman? She started at Monmouth College for a year or so which she found boring and dull and later finished her bachelors in education at Bradley University to become a teacher. Generally she didn’t like private schools because the students and faculty seemed pseudo-sophisticated; the University of Illinois, where she earned a masters degree in the summers, was her favorite. For a number of years she taught English at small country schools like Brimfield and Yates City, but her knowledge was so broad and so deep she could substitute, without hesitation, in virtually every field.

She was a good teacher, but a tough one. She gave A’s sparingly. An A was reserved for someone who did A work, not for the student who did the best work in the class. That was a difficult concept to grasp for many students and parents who couldn’t understand why there wasn’t at least one A in the class. She was a strict disciplinarian. She warned her classes against talking during an exam. When a future salutatorian asked a friend, innocently, for an eraser, she paid the price: her grade was lowered from an A to a B. Rules were rules. Her motto: strict standards + high expectations = high achievement. One of her students, a shy young farm boy from a high school graduating class of 20, went to Annapolis and became a nuclear submarine commander. (His earliest experience driving a vehicle was not plowing through the Atlantic but manipulating a John Deere tractor in a corn field.) Some of us grew weary hearing about him all the time and his accomplishments, but he was an inspiration to Helen. She used his example to light the fire beneath a number of young men who became corporate executives and young women who strayed from traditional female fields into more challenging ones typically reserved for males. She inspired students, especially those who were bright but lacked direction; she challenged them to do their best and make something of themselves. She was an early advocate for the community college, realizing that not all students needed or should attend traditional four-year colleges and that technicians of all kinds were important in our society, filling an important niche. No educational snob here. For those less gifted or motivated, Helen could be a pain when she wanted more from them than what they wanted to give. As one young woman said, “I wanted to be a nurse; she wanted me to be a doctor. She wanted more than I wanted to give.” Helen’s “push” encouraged many, but discouraged others who felt they were not one of her favorites. The fact is that practically all students were her “pets,” but for some her demands could be too much. Very quietly Helen and Raymond provided financial support for many young people unable to afford a college degree.

As a pre-teen, I first became acquainted with Helen when I carried sacks to her car from my family’s grocery store. She stood out because she was one of the few who were more interested in quality, particularly of meats and produce, than in price. She would usually ask the butcher to take a piece of round steak out of the meat case and grind it into hamburger in front of her eyes. She wanted her hamburger fresh; she wanted it lean. When she bought fresh produce, she had great respect for my father and his word, taking for granted his recommendations on peaches or apples or strawberries. If he said they were good, in her mind they were good. If he was uncertain, he would split an apple or cut a peach for her to taste, an offer he made to very few customers.

When I began having trouble writing in a number of college courses, my parents asked Helen if she would be willing to work with me. She agreed immediately. Little did I know that I would learn a lot more from Helen than how to write a correct, clear sentence. I can still remember going to her home for the first time, a 19th century two-story frame structure with a large porch running across the front. It may have been a dark color on the second floor and yellow on the bottom, nothing fancy, but carefully decorated, very comfortable. There was a large living room at the front with big down-filled davenports and chairs, some coming from as far away as Marshall-Field in Chicago. (I had difficulty understanding why anyone would go all the way to Chicago to buy a couch.) Since Helen and Raymond were the only ones in the house, the only time the furniture was used was when friends came for parties on some week-end evening. (They included the banker, some prominent businessmen, teachers, and others who loved books and ideas.) She had good taste; everything was color coordinated. Further in the back of the house was a dining room with a big table, seldom used for eating but often for storage: piles of new books, six or eight high, which she ordered regularly through the mail or checked out at the Peoria Public Library. (Who ever heard of buying books except at Christmas or having a card for a library twenty miles away?) Since she was often far behind in her reading, the table also held the latest issues of the New York Times (Sunday Edition), The New Yorker, and the Saturday Review, but seldom The Atlantic or Harpers. I had seen these publications in the library, but never in an individual’s home.

In the back of the house were the two most heavily used rooms: the kitchen which was fresh and white by 1952 standards, including a mysterious new appliance to me – an electric dishwashing machine – and a converted pantry about 11 by 12 by 5. It was absolutely marvelous. Helen and Raymond had taken a triangular pantry and converted it into a den-library-alcove with a wonderful fireplace on the narrow wall and floor-to-ceiling bookcases on the two wider walls. Warm and comfy. Helen had placed a daybed in front of the book shelves, allowing her to sit there, to read, to talk to guests who sat on the ledge in front of the hearth, and to watch the fire. The book collection was eclectic – everything from the Randle books on Lincoln to novels by Jane Austin and Charles Dickens, and to Schlesinger’s Coming of the New Deal. The best of the best, past or present. Perhaps what stood out most was a complete set of the Dictionary of American Biography. It was worn.

From 1956 or 1957 until 1962, I sat in that room by the fire on many Saturday evenings or Sunday afternoons, as Helen read and critiqued a paper which I was preparing for a class. At the beginning, the conversation ranged from comma splices to types of introductions or conclusions for essays on my last vacation or my response to Henry Kissinger’s Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy. In short, the criticism was fairly basic: the third sentence needed a semicolon, not a comma. The fourth sentence was awkward. The paper lacked a conclusion. Her criticism covered points I should have learned or should have been taught in high school, but gradually we moved from mechanics to ideas. Was the 20th century as bleak as Camus described in The Stranger? What was Melville trying to say to Ahab in Moby Dick? Gradually our discussion struck out into areas which were never discussed at my parents’ dinner table or which may have been too sensitive to discuss because the question would suggest doubts about some universal truths. According to my background, things were simple – they were right or they were wrong. Helen played devil’s advocate; why did I believe as I did? What evidence could I supply to counter her argument? We looked at issues from all points of view, and with the help of Will James’ Pragmatism, I was able to find some common ground between the left and the right. Things were not as simple as I once believed, but there were ways to compensate for the ambiguity of indefiniteness, for dealing with 20th century issues without resorting to 19th century thinking. Helen had grown from teacher to tutor, from professional to something, but probably not a friend. There was too much distance for that to happen.

This relationship, this tutorial continued for six years – from my freshman year at Knox College to the completion of my masters degree at the University of Illinois. I planned to major in business and run a grocery store; I ended up majoring in English and teaching at a community college. She was acutely aware of my fascination with the life of ideas and of my weaknesses in background, so she was very careful about steering me in the wrong direction. She didn’t try. Did she have an impact on my life? You decide. I read; I read all the time. I have subscribed to the New York Times since the late 50’s. I even rented a truck to move a couch from Crate and Barrel in Chicago to my home in Metamora, Illinois. I have written a great deal, and in retirement I’m continuing to do so.

Over the years, I saw Helen once in a while and talked to her on the phone, but our encounters were brief and occasional. We talked when I was writing a book, I brought my children for her to meet, and we had several discussions when I was working on a Ph.D. My life went on. So did hers.

A few years ago, when I learned that she, now in her eighties, was in the hospital, a voice spoke to me, saying “You’ve got to go see her.” Raymond was gone. No one was in the room. We talked about times past, about the papers, and the books, and conversations by the fireside. The voice said: “Tell her what’s on your mind.” I did. I told her that I owed her the world, that she was the most important academic influence on my life. She didn’t tear up, but I suspect there was a lump in her throat.

A week later she was gone.

Karl Taylor

Wonderful.

LikeLike

I’m glad you liked it. Don’t you like Amy’s work on the format?

LikeLike

I’m a friend of Amy Jo’s and I love reading your work. You have such a clear and comforting voice. Nothing quite like them. Thank you so much for sharing!

LikeLike

That shy young farm boy is my uncle

LikeLike

I also remember Mrs. Hart. She was quite the teacher! However, I think I may have put one over on her – or her on me. She was helping me pick a subject for the Lorado Taft Essay contest. She suggested several topics that I might be interested in and one of them was Wedgwood China. Can you guess which one a high school boy would pick! Wedgwood China was chosen as winner of the Lorado Taft Essay.

LikeLike

Weren’t you clever. Good to hear from you,

Doug.

LikeLike

Karl,

LikeLike

Karl, Thank you so much for preserving the past of Central Illinois in stories that are interesting, readable, and so nicely developed. So often, folks stop providing details long before I am ready for them to quit. You really do a nice job of elaborating without overdoing it. I enjoy not only your subject matter, but also your craftsmanship.It feels as though you are taking us home..

LikeLike

Sue, thanks for your comments, especially coming from someone special like you.

LikeLike

Karl,

I’ve enjoyed the article about “Helen” and an earlier article about Eddie Hahn’s Palace Theatre. Your writings about Elmwood citizens in the 1950’s have brought back many forgotten memories from growing up in Elmwood during that time. Please keep the stories coming.

LikeLike

Paul, I’m trying to remember who you are. Can you give me any clues? Thanks for reading my stores and for commenting. I have more stories to tell, just need the time to tell them. I’m working on a piece about the Elmwood Rocket Derby, about the basketball game in 1957 when Elmwood beat Canton in the opening round of the Canton Regional and the Elmwood Fall Festival. I live between Washington and Metamora, but my heart is in Elmwood.

LikeLike

Karl,

My parents were Lilah and Glenn Windish. Older sister Kay (Wagner) and brother Jim still live in the Elmwood area, but I left Elmwood in 1968. Education-wise, I graduated from ECHS in 1966, Canton Community College in 1968, Illinois State University in 1970, and the Army in 1972. I taught Agriculture at Lincoln-Way High School 1972 – 1983. I owned and operated a small family bakery in Tinley Park my in-laws had started back in 1948 from 1984 – 1996. My wife and I settled in her home town of Tinley Park, living in a house her maternal grandparents had built in 1948. I continued on working in bakery related sales and training until returning to teaching in 2002 at Minooka Community High School. My teaching experience at Minooka has been very enjoyable, combining most of my life’s training and experiences teaching first welding and small engines, then Foods and Culinary classes the past ten years. I became an adult learner in 2002 going to Governor’s State University, completing a Master’s in Educational Administration and certification as a Chief School Business Official. June 2017 is my planned “retirement” from my second whirl at teaching. Going back into teaching after close to 20 years in the workplace has given me a unique perspective about teaching. I consider myself semi-retired having holidays, Christmas and Spring breaks as well as Summers off. My wife retired in June after teaching Math 40 years at Lincoln-Way High School. My teaching tenure will be slightly over 29 years when I retire in 2017.

My currant hobbies are cars (1976 Avanti II and an 1989 Avanti convertible) and traveling. I have seven children ranging from 46 to 24 living in CO,IL, and KS. so that is a reason for some of the traveling. We did the Great American Tour this last June, driving the 1976 Avanti from St. Louis to Santa Monica CA following Rte 66. I’ve also started writing articles about the car shows and trips, recently getting published in the Avanti Magazine and an upcoming issue of Studebaker Driving Club’s Turning Wheels magazine.

Helen Hart Metz might roll over in her grave, learning one of the students she needed to see on a regular basis for rules infractions or behavior issues, actually become a contributing member of society and an educator.

LikeLike

Wonderful tribute to a great lady, however, at the time I was in high school I probably didn’t think so! I would never have graduated college were it not for her influence. I think many graduates feel that way. I also spent time at her house for the GAA slumber parties every year while I was in high school. They were great!

Karl, my folks are John and Lorene Maher. He was the mailman for Oak Hill and Brimfield for many years. We bought eggs from Edith when they lived on the Brimfield Blacktop (now Maher Road). My mother baked your wedding cake when you married Nancy. I have a twin brother, John and we were in the class of 1966 which is still the largest class to graduate from Elmwood. We will be celebrating our 50th year next spring as graduates.

Thanks so much for a great articles and jogging the many memories!

LikeLike

Beautiful story. Can you imagine if everyone had a Helen in their academic career? What a world we would live in.

LikeLike

This is a wonderful article. As an educator, I find her story very interesting. Do you know what years and where Mrs. Helen Hart Metz taught in the Brimfueld area?

LikeLike

Karl,

Your piece about my aunt near brought tears to my eyes. I remember sitting in that triangular room in the house that you describe. It’s directly across from the house that my grandmother and grandfather lived in. Of course my grandfather, John, died in 1922. I remember Bob Lott, Harry McFall, Roland Cady, and others dropping in. I loved it. I had no other experience of people just dropping in and talking. I also remember your family’s store. It was packed; the isles were narrow and the shelves were bulging with stock. If my memory is right the butcher was bald and gave me either bubble gum or suckers. And I remember you coming to the house for your tutorial with Helen. I can’t tell you how wonderful it all was for me. I need to make time to write down my memories. I’m 69 and still not retired. Incidentally my aunt was born on July 14th and she is named for a friend of my Grandfather who lived 2 houses closer to uptown, I have loads of memories to tell you about both her and Raymond.

LikeLike

Jim, it was great to hear from you. I remember you well, and I know you were one of Helen’s favorite people. I would love to hear more about Helen. Cathy Meyers (Harry McFall’s daughter) has also written a piece on Helen and others. You should call her and ask her to send them to you. We have had two cemetery walks and people have dramatized their lives. Cathy’s cell is 309-231-1588. My address is 1 Roth Court Metamora, Ill 61548 and my land line is 309-444-4154. If you have not read the piece in my blog on Nelson Dean Jay, I would encourage you to do so. Helen knew Jay and admired him. I’m working on his biography and doing a potential documentary. I’d like to have your comments. I look forward to hearing from you.

LikeLike